Andrew Revkin paid attention on his blog to what looks to be a really interesting report on the near future oil production. The report is written by Leonardo Maugeri, a fellow of the Belfer Center of Harvard University. In the past he worked for the Italian oil company Eni.

His homepage mentions that Maugeri for some time already does not think that the world is running out of oil:

Since the early 2000s, he was among the few who affirmed that the world’s oil was neither running out nor approaching its “peak-production.” He was also among the few who predicted the revolution of shale-gas and tight oil.

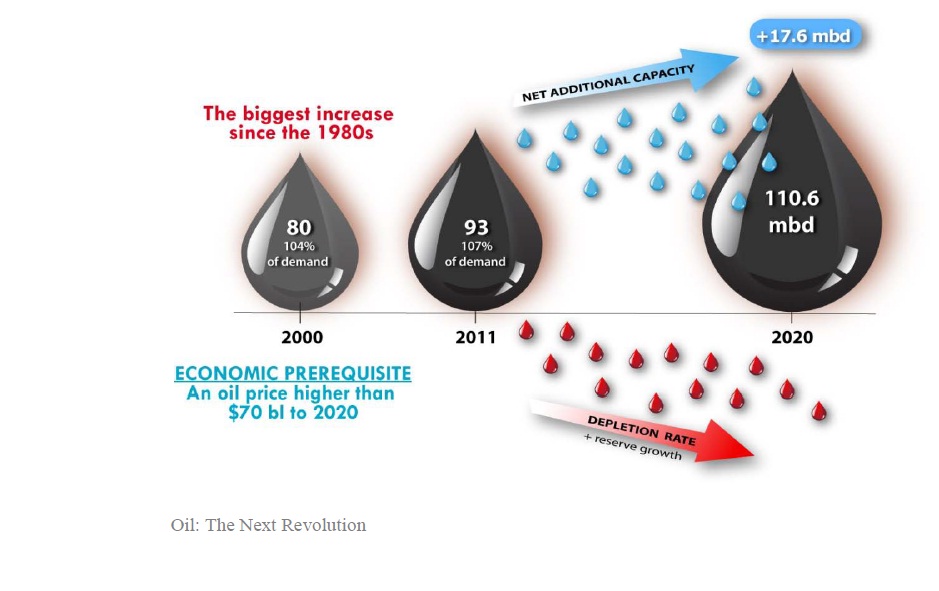

The main finding of the new report – Oil: the new revolution – is that the global production of oil could increase from 93 million barrels a day (mbd) now to more than 110 mbd in 2020. This estimate takes into account the depletion of reserves in conventional oil fields as can be seen in the picture below, which is taken from the report. The main prerequisite for this expected increase is that the oil price will stay above 70 dollar per barrel.

The Belfer Center has a press release about the report. Here is how it starts (bold mine):

Oil production capacity is surging in the United States and several other countries at such a fast pace that global oil output capacity is likely to grow by nearly 20 percent by 2020, which could prompt a plunge or even a collapse in oil prices, according to a new study by a researcher at the Harvard Kennedy School.

The findings by Leonardo Maugeri, a former oil industry executive who is now a fellow in the Geopolitics of Energy Project in the Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, are based on an original field-by-field analysis of the world’s major oil formations and exploration projects.

Contrary to some predictions that world oil production has peaked or will soon do so, Maugeri projects that output should grow from the current 93 million barrels per day to 110 million barrels per day by 2020, the biggest jump in any decade since the 1980s. What’s more, this increase represents less than 40 percent of the new oil production under development globally: more than 60 percent of the new production will likely reach the market after 2020.

Maugeri’s analysis finds that the gross additional production from current exploration and development projects in the world could produce an additional 49 million barrels per day by 2020, an increase equivalent to more than half the world’s current 93 million bpd. After adjusting that gross output increase for political and technical risk factors as well as the offsetting depletion rates of current fields, the analysis projects the net increase by 2020 to be about 17.5 bpd.

His study attributes the expected growth in oil output largely to a combination of high oil prices and new technologies such as hydraulic fracturing that are opening up vast new areas and allowing extraction of “unconventional” oil such as tight oil, oil shale, tar sands and ultra-heavy oil. These increases are projected to be greatest in the United States, Canada, Venezuela and Brazil. Maugeri also predicts a major increase in Iraq’s oil output as it regains stability, which will add new production in the Persian Gulf region — potentially destabilizing OPEC’s ability to manage output and prices.

Some excerpts from the executive summary:

Contrary to what most people believe, oil supply capacity is growing worldwide at such an unprecedented level that it might outpace consumption. This could lead to a glut of overproduction and a steep dip in oil prices.

(…)

This oil revival is spurred by an unparalleled investment cycle that started in 2003 and has reached its climax from 2010 on, with three-year investments in oil and gas exploration and production of more than $1.5 trillion (2012 data are estimates).

(…)

The most surprising factor of the global picture, however, is the explosion of the U.S. oil output.

Thanks to the technological revolution brought about by the combined use of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, the U.S. is now exploiting its huge and virtually untouched shale and tight oil fields, whose production – although still in its infancy – is already skyrocketing in North Dakota and Texas.(…)

The end of the summary presents some “important points” of which I will mention a few:

Oil is not in short supply. From a purely physical point of view, there are huge volumes of conventional and unconventional oils still to be developed, with no “peak-oil” in sight. The real problems concerning future oil production are above the surface, not beneath it, and relate to political decisions and geopolitical instability.

The shale/tight oil boom in the United States is not a temporary bubble, but the most important revolution in the oil sector in decades. It will probably trigger worldwide emulation over the next decades that might bear surprising results – given the fact that most shale/tight oil resources in the world are still unknown and untapped. What’s more, the application of shale extraction key-technologies (horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing) to conventional oilfield could dramatically increase world’s oil production.

The age of “cheap oil” is probably behind us, but it is still uncertain what the future level of oil prices might be. Technology may turn today’s expensive oil into tomorrow’s cheap oil.

Dear Marcel,

The headline “end of peak-oil” is not really supported by the content. What I read is that investments in production and technology ramp up production to the extent that a peak is postponed. That’s really great news. But it’s hardly an argument against the peak-oil theory.

That said, I would once again like to compliment you with your informative and insightful blog.

Rgds, Ernesto

Zeker een interessant verhaal, maar doet deels ook denken aan eerdere IEA-projecties, die de afgelopen jaren steeds naar beneden bijgesteld zijn. Een andere kijk hierop biedt deze recente notitie vanuit het IMF:

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12109.pdf

Ook daarin blijft de olieproductie tot 2020 groeien, maar ongeveer de helft minder dan in de projectie van Maugeri, met als gevolg een verdubbeling van de olieprijs tot circa 200 dollar/vat in 2020.

Hoe dan ook geeft dit alles aan dat een sterk klimaatbeleid nodig is om tot snelle CO2-reductie te komen.

Wat ik hier lees is interessant, maar lijkt mij wel doorspekt te zijn met allerlei veronderstellingen. Misschien valt schalieolie mee, misschien ook wel tegen, niemand kan daar nu iets zinnigs over zeggen. Kortom, ik ben het met Ernesto Spruyt eens dat de conclusie nog niet gestaafd wordt door de naar voren gebrachte feiten. Wellicht blijkt later dat hij gelijk heeft, wellicht ook niet. Bovendien zijn er zoals hij zelf al aangeeft grotere invloeden die veel meer invloed zouden hebben op de aangekondigde -maar nog niet vastgestelde-piekolieproductie; geopolitieke conflicten en langdurige recessies zouden daarop weleens inderdaad grotere invloeden kunnen hebben dan… Lees verder »

Olie produceren uit teerzand en schalie kost erg veel energie.

Voor conventionele olievelden bedraagt de EROEI (Energy Return on Energy Invested) meer dan 10:1.

Schalie-olie en teerzandolie halen waarschijnlijk een EROEI van 3:1. Van elke drie vaten teerzandolie wordt er al één verbruikt tijdens de winning.

De toename van 17,6 miljoen vaten per dag betekent dat er effectief maar 11,8 miljoen vaten bijkomen, die nuttig besteed kunnen worden.

Dit verhaal is bestemd voor investeerders en het doel is om veel geld los te krijgen voor schalie-olie-projecten. Oliedeskundigen zullen dit verhaal ongelezen in de prullenbak smijten.

En Hans geeft het goede antwoord. Gaston, wat zijn de prijzen?

George Monbiot hierover:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/jul/02/peak-oil-we-we-wrong

En ter aanvulling voor iedereen die graag voorspellingen wil doen toekomstige energievoorziening, het boek “Energy at the Crossroads, Global Perspectives and Uncertainties” van energie-expert Vaclav Smil is een must-read, al was het maar omdat hij laat zien – basis van 50 jaar en langer aan voorspellingen over energieverbruik en energieproductie – je deze voorspellingen met zeer grote korrels zout moet nemen. Al decennia lang blijkt dat geen enkele individu en geen enkel instituut dit zelfs maar 10 jaar vooruit met enige betrouwbaarheid kan voorspellen.

http://www.amazon.com/Energy-Crossroads-Global-Perspectives-Uncertainties/dp/0262194929

HB

HB

Alles wat Smil schrijft is razend interessant, ik heb vorige week nog een tijdje op zijn homepage rondgedoold.

Ik kwam van de week ook dit uitstekende stuk tegen:

http://spectrum.ieee.org/energy/renewables/a-skeptic-looks-at-alternative-energy

gr Marcel

TOD legt uitgebreid uit waarom Maugeri er naast zit.

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/9327